The Cold War under the neon lights

The Warsaw Neon Museum recovers the lights with which, from the 1950s until its final collapse, the communist regime tried to portray a modern and cosmopolitan outlook and which left a wide range of examples of graphic design created by the best artists and architects of the time.

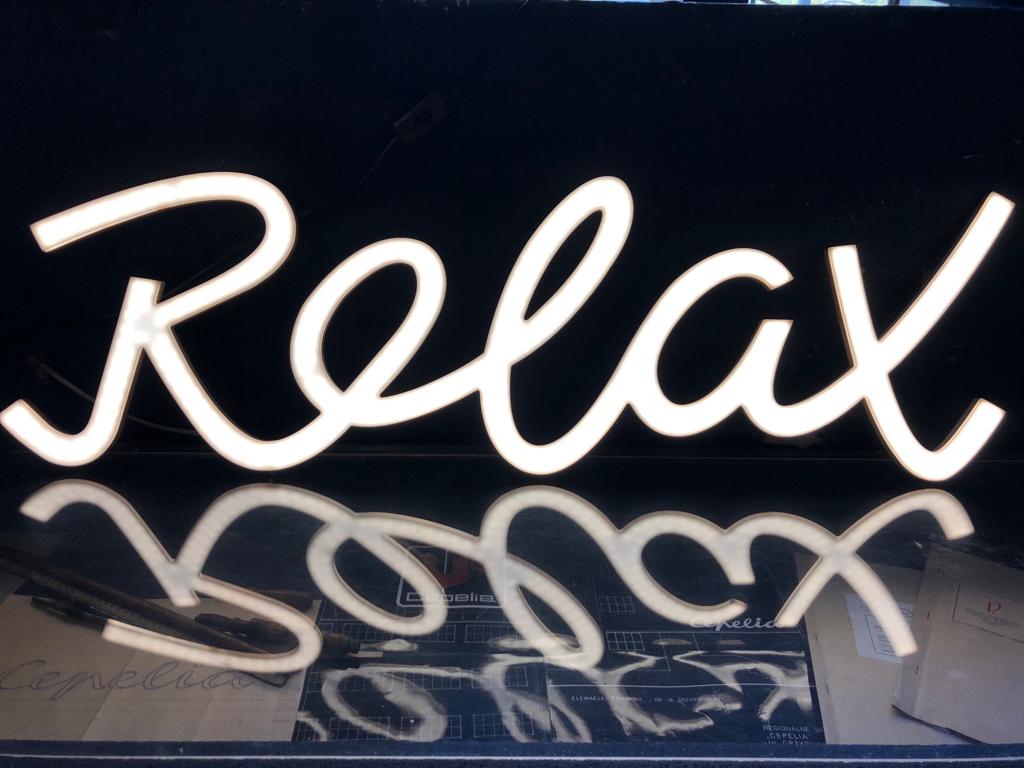

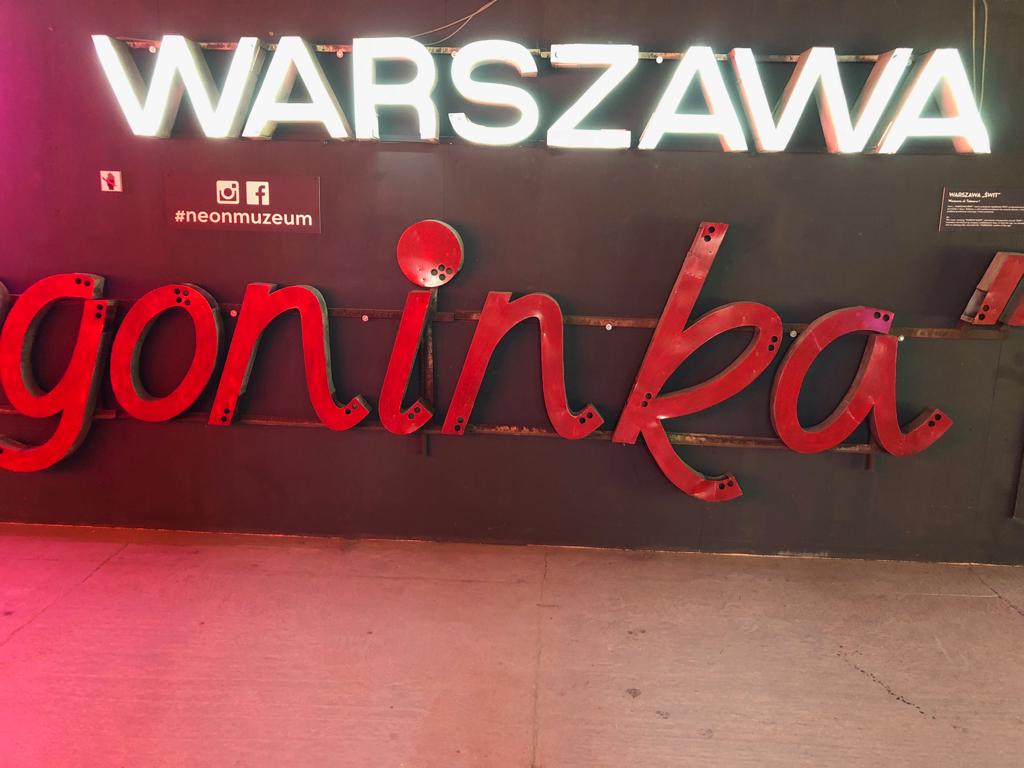

Neon light coloured the grey tones of Stalinism in Warsaw during the 1950s. The city was «neonized», a term used to explain the multiple meanings behind these gas-filled tubes that illuminate shops, hotels, cinemas and other city buildings. Neon was political, it was fun, it was a look to the future, it was the vanguard of design. Today these neon lights are kept in one of the most curious museums in Europe. The Neon Museum is housed in a small building within a design complex called the Soho Factory in the emerging Prague district of the Polish capital.

Neon was political, it was fun, it was a look to the future, it was the vanguard of design

Post-war. Warsaw was grey. The Polish capital was the colour Stalin forced it to be. The city, destroyed during the Second World War by the Nazis, was rebuilt by Stalinism, with its long, wide avenues, block buildings, bathed in socialist realism and presided over by the Palace of Culture and Science, a gift from Moscow that today continues to mark the skyline of the city threatened by modern glass skyscrapers. It was a city that can still be clearly perceived today.

Stalin died in 1953. Khrushchev succeeded him and made public the atrocities of the communist dictator. It was a minimal thaw (in fact, Khrushchev fell soon after and orthodoxy returned through Brezhnev), but it was a window of opportunity which satellite countries took advantage of. And that’s where neon came in.

“Neonisation” was a high-level political decision. The Polish Ministry of Domestic Trade established a series of regulations in its favour and neon artists set out to illuminate the city, based on cities such as London, Paris, Hamburg and even Warsaw before the war.

There were regulations, rules on colours, typeface and other technical aspects. It is not surprising that the bloc in which Poland was aligned emerged from socialist realism, consisting of a set of strict rules on what art should be. Although even then, they strictly reflected what it should not be. So there was no shortage of rules.

“Neonisation” was a high-level political decision

Warsaw wanted to become one of the major European cities. More than a commercial interest, it was art and architecture that inspired the designers. The politicians were also interested in displaying a different economic and cultural vision from the one Stalinism had left in the city.

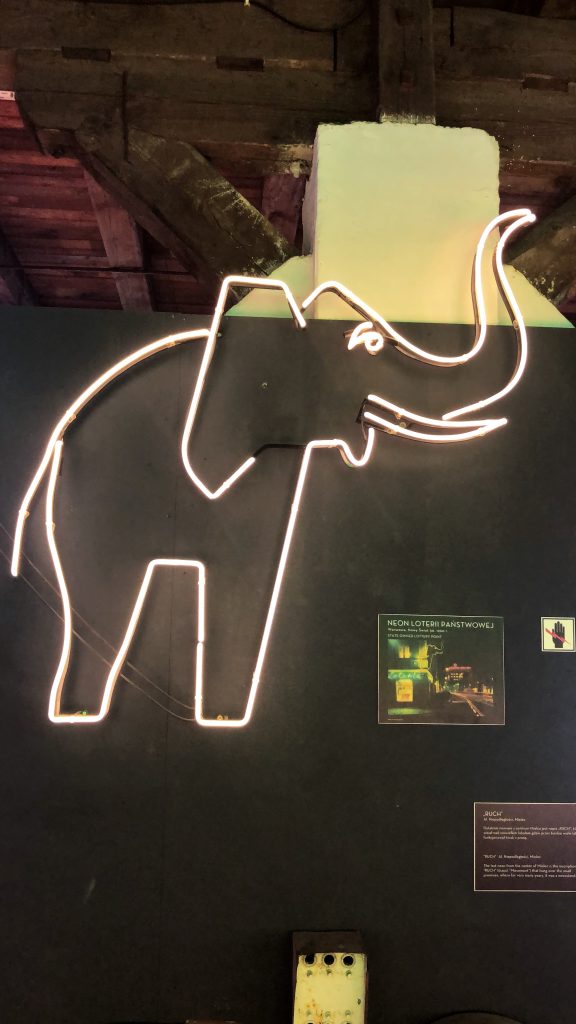

The Neonisation Period of the 1950s saw how the best architects and visual artists dedicated themselves to lighting the streets. The so-called «Neon Group» planned the lighting of Pulawska Street, south of the city. While Eleonora Sekrecka and Zygmunt Stepinski were responsible for neonising the important Marszalkowska Street, where you can still see classic neon lights, such as those of the Luna cinema or the Prasowy milk-bar brightening up the enormous grey buildings. Some of the artists who formed the well-known Polish Poster School also participated.

It was art and architecture that inspired the designers

Cinemas, shops, pharmacies, hotels, libraries were a colourful note against the grey which, despite everything, was still the uniform of the Polish capital. Artists and politicians probably saw the phenomenon differently. The firsts found a modern form of expression; the latter saw the perfect vehicle for their propaganda of a prosperous and cosmopolitan nation that, despite their efforts, fooled only few.

That was the tone of the Cold War in Eastern Europe. In the sixties and seventies, the bureaucracy drowned the neons. The conservatism that marked Moscow left its mark with increasingly harsh demands. At the end of the seventies the economic crisis hit the country hard, the opposition grew under the trade union organization Solidarity and the government responded in 1981 with martial law under the iron rule of General Jaruzelski. During the year and a half of martial law, most of the country’s neon lights were switched off by the authorities and the streets returned to the dirty grey of Stalinism. The «neonisation» party was over.

Democracy arrived under the influence of Perestroika in 1990 when Lech Walesa won the elections, many of the neon lights that populated the city were catalogued as a remnant of the dark communist era and were destroyed. Years later, stripped of their political significance, the neon lights are once again seen as an example of electro-design, art in the heart of the city and an architectural complement that is worth knowing, valuing and protecting.

The Warsaw Neon Museum includes in its collection some of the most important neon lights in the capital and other cities of Poland. At the same time, it has launched a campaign called «Action Renovation» to try to preserve the neon lights that still remain in the city.